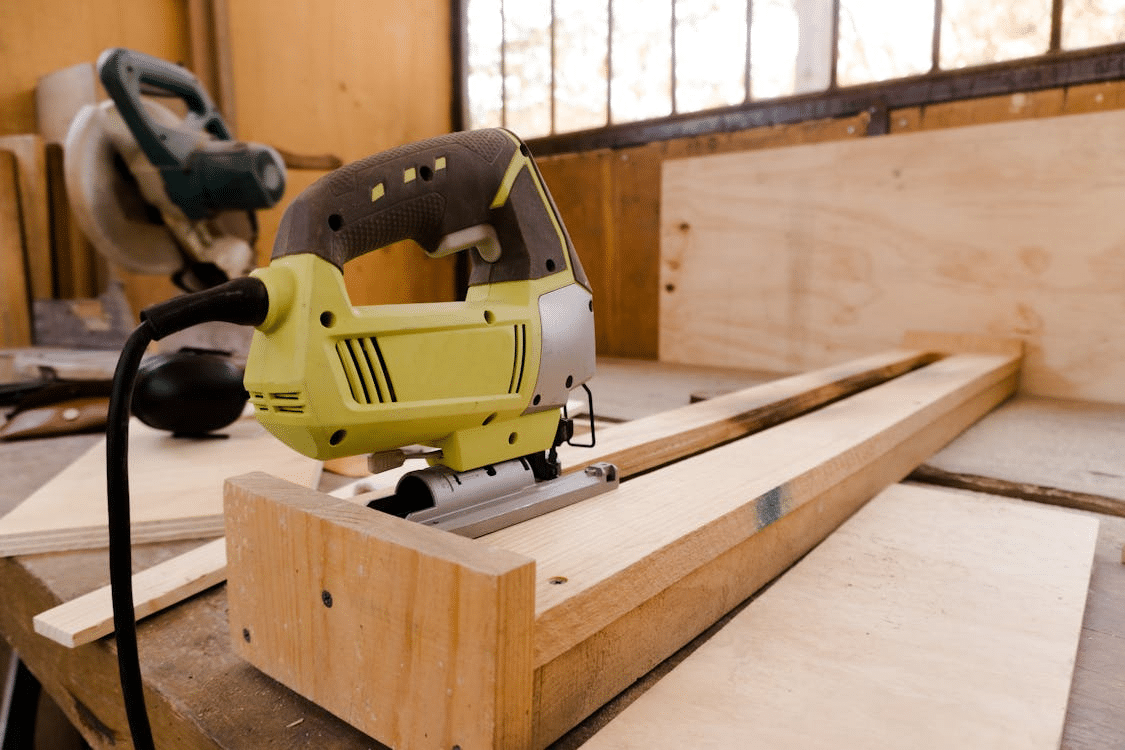

Most power tools don’t fail randomly. They fail in patterns. The problem is that people troubleshoot emotionally instead of sequentially. A tool stops, frustration spikes, and the assumption becomes catastrophic damage. In reality, the majority of “dead” tools haven’t suffered a fatal failure at all. They’ve lost continuity somewhere simple, common, and predictable.

The fastest way to get a tool running again isn’t guessing harder – it’s checking things in the right order, starting with the failures that happen most often and cost the least to fix.

Start Here: The Failure Almost Everyone Skips (Carbon Brushes)

Before you spiral into “this thing is toast,” stop right here. Carbon brushes are one of the most common, least checked reasons a power tool stops working, especially in corded tools and older cordless models. They get missed for a very human reason, not a technical one.

When a tool dies instantly, the brain jumps to “motor’s fried.” That feels final. Brushes don’t give drama. They don’t smoke. They don’t complain. They just… disappear. That’s how even experienced people get fooled.

Repair center service data backs this up. Carbon brush wear accounts for roughly 20-35 percent of non-battery-related power tool failures in homeowner-grade tools after 3-5 years of intermittent use. That’s not an edge case. That’s common.

Here’s what’s actually going on. Carbon brushes are sacrificial electrical contacts made of graphite, sometimes graphite-copper blends. They press against the commutator so electricity can jump from stationary wiring into a spinning armature. Every rotation scrapes off a microscopic amount of carbon. That’s not misuse. That’s design. It’s planned consumption, like brake pads on a car.

And the motor is spinning fast. Really fast. A brushed universal motor typically runs 18,000-25,000 RPM, which means a single brush sees millions of sliding contact events per hour of runtime. Wear is inevitable (source).

What matters is length, pressure, and surface geometry. As brushes get shorter, the springs behind them lose force. Less force means sketchy contact. Sketchy contact causes arcing. Arcing eats the brush faster and dumps heat right into the commutator. Once spring force drops below spec, contact resistance can spike by over 300 percent, and the motor stops cleanly, like someone pulled the plug.

You’re likely looking at brushes if this sounds familiar:

- The tool stopped suddenly after long use but shows no other damage, no slow fade, nothing. Brushes often cross the failure line and die within a single session.

- The motor smells faintly metallic or ozone-like, not like burnt insulation. That ozone smell comes straight from electrical arcing.

- The tool worked perfectly until the exact moment it didn’t, even under normal load.

- Restart attempts do absolutely nothing, even though power at the outlet or battery is confirmed.

Checking brushes is quick. Unplug the tool or pull the battery. Find the brush caps, usually small screw-in covers on opposite sides of the motor housing. Pull the brushes gently. Measure the graphite itself, not the spring.

If you’re seeing less than 5-7 mm of usable carbon (varies by tool), replacement is overdue. Most brushes start at 12-20 mm, and manufacturers expect replacement when you’re down to 25-40 percent remaining. Uneven wear between the two brushes looks scary but usually just means commutator imbalance. Still fixable.

When brushes are the issue, replacement usually brings the tool straight back to life because nothing else has failed. Windings, bearings, gears – all fine. There’s no firmware reset, no break-in ritual. Power flows again. Field tests show restored current draw returning to 95-100 percent of factory specs after brush replacement.

If you want to skip guesswork, TopDealsOnline carries carbon brushes matched by tool model and dimensions. That detail matters more than people think. A 1 mm mismatch can shorten brush life by 20-30 percent just from poor contact geometry.

This one check alone saves a lot of perfectly good tools from the landfill. Once brushes are ruled out, you can move on without that “what if” looping in your head.

The Moment You Realize the Tool Isn’t Dead – It’s Deciding Whether to Cooperate

When a power tool goes dead mid-task, the real decision isn’t repair versus replace. It’s simpler and more important than that. Did something break, or did the tool decide to protect itself? That question saves time, money, and stress.

People who troubleshoot for a living aim to identify the failure mode in the first 60-90 seconds. Once you know how it failed, you stop chasing ghosts.

Clean, sudden shutdowns almost never mean the motor exploded internally. Electric motors are stubborn. They die for real only after prolonged overheating, overvoltage, or insulation breakdown. When a tool cuts out instantly, something upstream said “no.” Protection circuits can trip in under 100 milliseconds, faster than you can process what happened.

Look closely at the moment it failed. Machines communicate through timing and context. An instant stop under resistance points toward current interruption or thermal protection. A slow fade, pulsing, or hesitation suggests voltage sag or failing contacts, and even a 10 percent voltage drop can cut motor torque by over 20 percent. Total silence from the very first trigger pull usually means an open circuit or safety interlock.

This distinction matters because it keeps you from tearing into a gearbox for no reason. If the tool died ripping wet lumber or drilling masonry, load-based protection is likely. If it died while idling, power continuity is suspect. Idle current draw is often under 15 percent of rated load, so that context changes everything.

Experts think in failure modes, not symptoms. Once you identify the mode, the list of possible causes collapses fast, and the next obvious question becomes whether electricity is actually reaching the motor consistently.

When Power Is the Real Problem – Not the Tool You’re Holding

Most “dead tools” aren’t dead. They’re starved. Voltage showing up doesn’t mean usable power is arriving. Motors want amperage under load, and any bottleneck creates failure that looks internal. A motor rated at 12 amps may try to pull 18-20 amps momentarily at startup or under heavy load.

Corded tools: follow the electrons

Homes aren’t laboratories. Extension cords add resistance. Old outlets lose grip tension. Internal strain reliefs fatigue copper over time. Every one of these quietly restricts current. Add 25 feet of 16-gauge extension cord, and you can lose 5-10 percent of available current without noticing.

The usual trouble spots show up where movement and heat live together. Conductor necking happens inside cords near the plug or tool entry, where bending breaks strands invisibly. A cord can lose over 50 percent of its current-carrying capacity and still look fine. Loose outlet contacts heat and cool repeatedly, increasing resistance each cycle. Shared circuits matter too. A 15-amp breaker circuit gets overwhelmed around 1,800 watts, so add a heater, compressor, or shop vac and your tool starts fighting for scraps.

A lamp test only confirms voltage exists, not that current can flow. It’s still useful for ruling out dead outlets. For intermittent problems, gently flex the cord while the tool is switched on. If behavior changes, the cord is lying to you.

Cordless tools: batteries lie by omission

Lithium-ion packs fail chemically before they fail electrically. Internal resistance creeps up. Voltage looks fine sitting still, then collapses under load. After 300-500 charge cycles, internal resistance can double.

That’s why you see this pattern: the tool starts, then instantly quits when torque is demanded; LEDs insist the battery is charged; the charger hits “full” suspiciously fast. Charging time can drop 30-50 percent when capacity is gone.

Swapping batteries answers the question in seconds. If all batteries behave the same, look at the charger or internal power electronics. Once power delivery is genuinely solid, then it makes sense to blame the tool itself.

The Hidden Safeties That Shut Tools Down Without Warning

Modern tools are full of silent guardians. They feel rude when they trip, but they exist for a reason. Replacement motors often cost 40-70 percent of a new tool’s retail price, so manufacturers would rather annoy you than kill the motor.

Thermal shutdown feels like betrayal

Motor windings are coated in varnish rated to specific temperature classes. Exceed that rating and insulation breaks down, turns short, motor’s done. To prevent that, tools shut themselves down when internal temperatures cross a threshold, commonly 105°C to 130°C.

Heat spikes when blades go dull and torque demand climbs, when feed rate gets aggressive, or when dust blocks ventilation. Clogged airflow alone can raise internal temperatures 20-30°C faster than most people expect (source).

If the tool comes back after cooling, nothing broke. It protected itself.

Trigger and lock mechanisms fail quietly

Triggers are low-voltage control parts telling high-current systems what to do. Dust, tired springs, or carbon buildup on contacts can stop the signal entirely. Microscopic pitting alone can raise resistance enough to prevent relay closure.

Slow trigger pulls, cycling the safety lock, or blasting compressed air don’t fix the problem, but they change geometry just enough to reveal it. If behavior changes, the diagnosis is clear.

Once safeties are ruled out, you’re down to physical resistance.

When the Tool Wants to Turn – But Something Is Physically Stopping It

Mechanical resistance often masquerades as electrical failure. Motors respond to resistance by pulling more current. During a stall, current can spike 150-200 percent above rated load, tripping protection instantly.

Accessories are the quiet villains here. Pitch buildup, corrosion, or impact damage locks things up more often than people admit. Service logs show accessories account for a majority of “no-spin” complaints.

Pull everything off. Spin the output by hand. Smooth rotation points to motor health. Grinding or stiffness narrows the fault to bearings, debris, or the gear train.

Gearboxes tell stories through sound, or the lack of it. Clicking under load suggests tooth deformation. Sudden free-spinning means stripped engagement. Total lockup with no noise often means foreign material intrusion. Metal fragments smaller than a grain of sand can jam planetary gearsets.

At this point, the problem isn’t technical anymore. It’s economic.

The Repair-or-Replace Line Most People Cross Too Early

Opening a tool feels decisive. It can also destroy remaining value. Improper reassembly accounts for a large share of failed DIY repairs.

Repair usually makes sense when the tool cost exceeded $150 new, replacement batteries exceed $60, the failure traces to consumables or switchgear, or the tool lives in a shared battery ecosystem.

Brands like DeWalt, Milwaukee, and Ryobi build modular systems with documented part trees. Brushes, switches, and cords often cost under 10 percent of replacement value. That’s not nostalgia. That’s math.

Replacement wins when windings smell acrid or insulation is visibly darkened, gear teeth are missing or housings cracked, or repair costs approach 50 percent of replacement value.

Time matters. Momentum matters. Confidence matters.

Regaining Momentum Without Guessing or Second-Guessing

A stalled tool messes with your head more than your schedule. The fix isn’t heroics. It’s sequence.

Work through failures in this order:

- Carbon brushes

- Power delivery (outlet, cord, battery, charger)

- Protection systems (thermal, trigger, lockouts)

- Mechanical resistance (accessories, gears)

- Component economics (repair versus replacement)

Most experienced techs solve the majority of tool failures in the first two steps. No panic buys. No rage returns. Just forward motion.

When the right decision clicks, things feel the way they should again. Controlled. Predictable. Like the tool is finally working with you instead of daring you to quit.